Wolves WolvesWolf History, Conservation, Ecology and Behavior

[www.wolfology.com]

|

Mexican Wolf Recovery: First Phase

Jason Manning

|

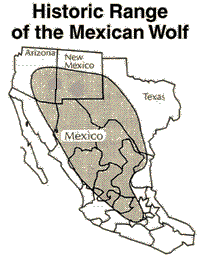

The Mexican wolf (Canis lupus baileyi) is not only the most rare subspecies of North American gray wolf, it is also the most genetically distinct. The "lobo" once ranged throughout the northern half of Mexico into southern Arizona, New Mexico and Texas. The last wild Mexican wolves in the United States were killed in 1970, and the lobo was placed on the Endangered Species List in 1976. A few remained in the wild in Mexico; the last verified sighting occurred in Chihuahua in 1980. Loss of habitat, a decrease in prey numbers, and aggressive predator control resulted in the lobo's near demise.

The U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (FWS) hired wolf trapper Roy McBride in 1976 to capture and bring back alive as many Mexican grays as he could find. Searching for four years, McBride could find only five -- four males and a pregnant female. These animals formed the basis for a captive breeding program. A Mexican Wolf Recovery Team was established in 1979 and three years later produced a recovery plan, approved by both Mexico and the U.S., which called for reestablishing a self-sustaining wild population of 100 Mexican wolves in the American Southwest. The International Union for Conservation of Nature proclaimed Mexican wolf recovery the top priority in worldwide wolf conservation. The U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (FWS) hired wolf trapper Roy McBride in 1976 to capture and bring back alive as many Mexican grays as he could find. Searching for four years, McBride could find only five -- four males and a pregnant female. These animals formed the basis for a captive breeding program. A Mexican Wolf Recovery Team was established in 1979 and three years later produced a recovery plan, approved by both Mexico and the U.S., which called for reestablishing a self-sustaining wild population of 100 Mexican wolves in the American Southwest. The International Union for Conservation of Nature proclaimed Mexican wolf recovery the top priority in worldwide wolf conservation.By 1995 the captive population had increased to 91 lobos in 19 facilities in the U.S., with an additional 13 animals at five Mexican facilities. That same year, wolves in two unofficial breeding programs -- the Ghost Ranch lineage (U.S.) and the Aragon lineage (Mexico) -- were included in the recovery plan after mitochondrial and nuclear DNA analysis verified their origins. This added 26 more wolves to the total captive population. The Mexican wolf had been brought back from the brink of extinction. Now the question was: Could they be successfully reintroduced into the wild?

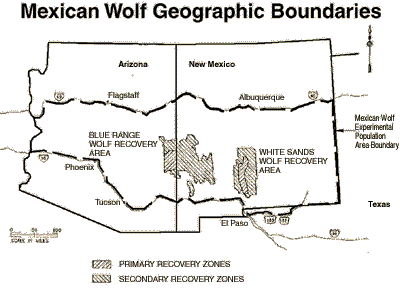

The first step toward that goal was feasibility studies of possible reintroduction sites. Among those considered was Big Bend National Park, but when the Texas Parks & Wildlife Department refused to cooperate, the focus turned to the Blue Range area of Arizona/New Mexico and the White Sands area of New Mexico. The former, about 7,000 square miles in size, includes the Apache and Gila National Forests and was deemed the best site because it offered the greatest prey diversity as well as the rugged mountain woodlands that lobos prefer.

The reintroduction was vigorously opposed by politicians and stockgrowers, the latter including three Apache tribes on reservations near the Blue Range. The stockgrowers talked as though bringing the wolf back would destroy the livestock industry in the area -- even though studies predicted that 100 wild wolves would kill only 34 cows annually. In response to concerns about predation of livestock, a wolf compensation fund was established. The "experimental, nonessential" designation assigned to the released wolves would allow greater management flexibility; problem wolves could be removed by the authorities, and livestock owners could kill a wolf caught in the act of preying on livestock on private land. Polls showed that the public in both Arizona and New Mexico strongly supported wolf recovery; 77% of 3,221 Arizonans surveyed were in favor, with only 13% opposed and 10% undecided. These results influenced the Arizona Wool Producers and the Arizona Cattle Growers Association, which announced they would no longer oppose reintroduction.

The FWS released its Final Environmental Impact Statement in 1996 and published its Final Rule on the recovery plan in the Federal Register (12 January 1998, Vol. 63, No. 7, pp 1752-1772) after Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt formally approved the plan. A pre-release facility was constructed at Sevilleta National Wildlife Refuge 60 miles from Albuquerque, NM, where the wolves selected for release could be evaluated and acclimated. The recovery plan called for a primary release of fourteen family groups in the Blue Range Wolf Recovery Area over a period of five years. It was hoped that in 7-10 years a self-sustaining population of 100 wolves would be in place. If necessary to achieve that goal, a secondary release of five family groups over a period of three years would occur in the White Sands Wolf Recovery Area. (With about 1,000 square miles of prime wolf habitat, White Sands could support approximately 20 wolves.)

Dispersal of wolves into secondary recovery zones would be allowed within an experimental population boundary that includes central Arizona, the southern half of New Mexico, and a portion of Texas lying east of El Paso and north of U.S. Hwy. 62/180. According to the Final Rule, any wolf found outside this boundary area would be presumed "to be of wild origin and full endangered status," while those found within it would be counted as part of the experimental population.

Above: The experimental population boundary of the Mexican Wolf Recovery Plan. In 1996, Defenders of Wildlife proposed adding Big Bend National Park in Texas to sites chosen by the FWS.

By 1998, the year of the first release, there were 176 Mexican grays held at 32 facilities cooperating in the Mexican Wolf Species Survival Plan. Eleven of the lobos were released into the Blue Range in January 1998. By the end of that year five had been shot to death, three by "terrorists who are trying to sabotage the program," according to a spokesperson for the Interior Department. In April the first casualty, #156, was shot by a camper, who was not prosecuted. On the opening day of bear hunting season in August, #174 (the first Mexican wolf to bear a pup in the wild in half a century) was shot while feeding on an elk. A 2-year-old female, #493, was found shot in October. In November, two male yearlings, both from the Hawk's Nest Pack, were found shot dead, one near the Arizona-New Mexico border and the other on the White Mountain Apache Reservation. Rewards were offered for information leading to arrests and convictions in the last three shootings.

Five more wolves were recaptured: three females (#128, #494 and #511) and two males, Hawk's Nest #131 and Campbell Blue #166. The latter were to be paired with new females and readied for release back into the wild. Wolf #127 was missing and presumed dead, as was the pup born in the wild to #174. Secretary Babbitt announced that a second release would occur; the Mexican wolf, he declared, was here to stay. Meanwhile, the New Mexico Cattle Growers Association filed suit in federal district court to stop the reintroduction, arguing that wolves already existed in the recovery area, and that the animals being released were actually hybrids.

As 1998 drew to a close, no one could deny that the first release had been a failure. The fate of the entire recovery plan was in question.

For more information write to

Mexican Wolf Recovery Coordinator

USFWS · PO Box 1306 · Albuquerque, NM 87103

Facilities containing captive Mexican wolves (as of 2000)

Alameda Park Zoo-Alamogordo, NM

Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum-Tucson, AZ

Belle Isle Zoo-Royal Oak, MI

Binder Park Zoo-Battle Creek, MI

Cheyenne Mountian Zoo-Colorado Springs, CO

Columbus Zoological Gardens-Powell, OH

Dakota Zoo-Bismark, ND

El Paso Zoo-El Paso, TX

Fort Worth Zoo-Fort Worth, TX

Fossil Rim Wildlife Center-Glen Rose, TX

Freeport McMoran Audubon Species Survival and Research Center and Wilderness Park-New Orleans, LA

The Living Desert-Palm Desert, CA

The Living Desert State Park-Carlsbad, NM

Minnesota Zoo-Apple Valley, MN

New York Zoological Society-Bronx, NY

Phoenix Zoo-Phoenix, AZ

Rio Grande Zoo-Albuqurque, NM

Sedgewick County Zoo-Wichita, KS

Wild Canid Survival and Research Center-Eureka, MO

Wolf Haven International-Tenino, WA

Lincoln Park Zoo-Chicago, IL

Navajo Nation Zoo and Botanic Park-Window Rock, AZ

Hillcrest Park Zoo-Clovis, NM

Houston Zoo-Houston, TX

Southwest Rehabilitation and Education Foundation Inc.-Scottsdale, AZ

La Fundacion Chihuahuense De La Fauna-Chihuahua, Mexico

La Reserva De La Biosphera "la Michilia"-Durango, Mexico

Centro Ecologico De Sonora, Hermosillo-Sonora, Mexico

Zoologico De Chapultepec-Ciudad Mexico, Mexico

Parque Zoologico De San Juan De Aragon-Ciudad Mexico, Mexico

|

Copyright 2002 Jason Manning All Rights Reserved

Feel free to duplicate for educational purposes.

|